Rosemary Hannan

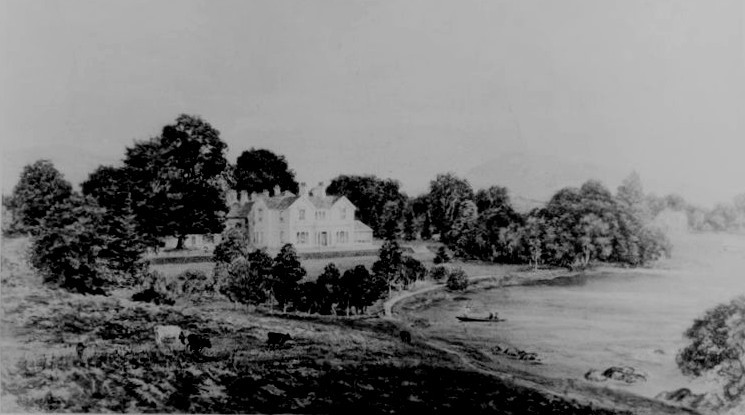

Waterpark House 1890. Painting by H.Clifford Warren showing a Shannon cot or punt and the riverside walk (Weir, H.L. 1989 ‘Houses of Clare’)

“Waterpark” was the home of the Bindon Family. It was located on the estate of Sir Hugh Dillon Massy beside the River Shannon. (Weir, 1989)

In 1754 the linen trade was actively promoted outside of Ulster and landlords were becoming interested in developing their estates.

Hercules Browning Arrives in Waterpark

From the beginning of the 18th Century, skilled ‘bleachers’ came to Ireland from Holland with the Huguenot linen settlers. Grants were given to establish bleach works by the Linen Board (Gill, 1925). Bleaching became a very important stage in the process of making linen. It was managed by men of substance who were large employers. Hercules Browning was one of those men.

The first official record of Hercules Brownriggs / Browning (his surname appears with the varied spelling in documents) was noted in a report of the Linen Board by Robert Stephenson in 1760. This report shows Hercules Browning, Limerick was an applicant for the Linen Board’s three premiums (O’Connor, 1989). Browning had an outlet at John Street, Limerick where he received brown linen for processing.

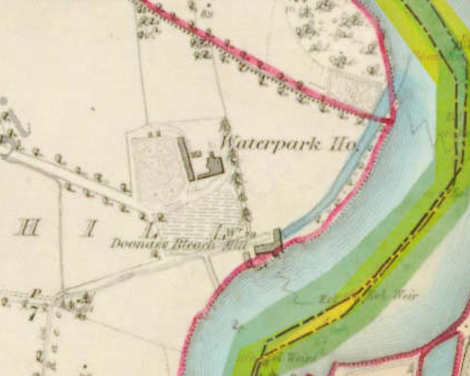

Waterpark House and Doonass Bleach Mill on the first edition OS map c.1840.

‘Data from the historic maps gallery accessed through the Heritage Maps Viewer at www.heritagemaps.ie, 1-2-2020’.

According to the local historian, Freddie Bourke (1998), Hercules Brownriggs from Northern Ireland built a large linen bleach mill at “Waterpark”, Doonass. He employed experienced bleachers from Northern Ireland. Brownriggs also held leases of land in the townlands of Aughboy and Kildooras. These townlands, at that time, had bogs which provided good quality turf, which was used at the mill during the bleaching process. Brownriggs settled his Northern employees, the Johnsons, the Fergusons and Caswells, to name a few, in Kildooras and Coolistigue on smallholdings of land (1-5 acres). (Bourke, 1998)

Brownriggs-Massy Articles of Agreement relating to Summerhill house (Courtesy of Matthew Potter, Curator, Limerick City Museum).

Further records demonstrate Brownings activities:

- John Ferrar’s Trade Directory (1769)

- John Ferrar’s History of Limerick (1787)

- Deeds Conveying to Massy property at Summerhill County Clare and Bleach Yard Farm (1789)

- Hercules Browning subscribes towards completing the Limerick navigation of the Shannon (Erinagh Canal) (1793) (Source: waterwaysireland.com)

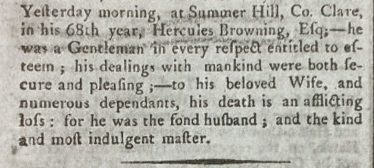

Brownings Death Announcement (Limerick Chronicle 30/4/1796)

On 30th April 1796, Hercules Browning’s death is announced in the Limerick Chronicle.

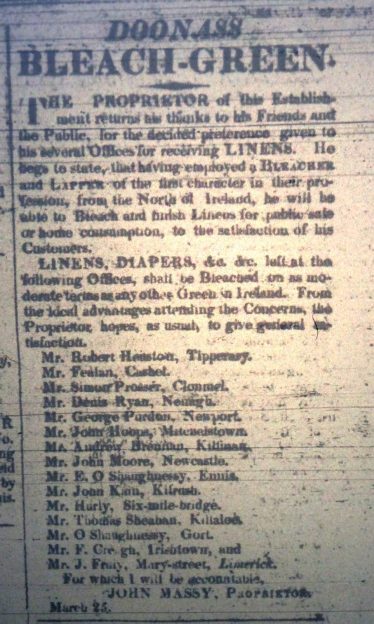

Bleach Mill Advertisement signed by John Massy (The Clare Journal and Ennis Advertiser 30/3/1820)

From Browning to Massy

The next record of the bleach mill is in 1820 in the Clare Journal and Ennis Advertiser. The advertisement for the bleach mill is signed by John Massy, Proprietor.

Samuel Lewis (1837) notes the extensive bleaching establishment at Doonass and it is clearly identified on the first edition 6-inch Ordnance Survey map of 1840. (Lewis, 1837)

Hugh Dillon Massy’s Deed of Assignment and Mortgage states that in 1844 the Bleach Mill gave good employment to the locality. (1844 cited in Bourke F 1998)

John Bindon takes ownership

It appears the mill survived the Famine years and in 1847, the proprietor of the Mill was John Bindon, who was resident in Waterpark House. He advertised its services as “the largest public bleach green in Ireland” on the Limerick Chronicle November 1st, 1847.

The harvesting and scutching of the flax crop was exceedingly labour-intensive and was best suited to cultivation on smallholdings. As rural out-migration became a feature of life in post-famine Ireland and labour costs increased, the flax crop could no longer be as profitably harvested by a family, whose sons and daughters were now settled outside the country. It was compounded by the steady increase in farm sizes and the elimination of many of the smallholdings upon which flax had been traditionally grown. (Smith, W.J, 1988)

The Bindons of Waterpark appear to have suffered a financial setback which forced them to close the bleach mill in 1849. 240 people were made redundant from their jobs in the mill. (Bourke, F, 1998). The mill was sold to John and Maria Quinn and they started a corn mill. (http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie, 2020)

What was the process at the bleaching mill?

Bleaching was a very important part of the linen industry. It took place on the bleaching greens which were large tracts of land along the banks of rivers that had a good flow of water in summertime. The linen was boiled and rinsed up to a dozen times. The linen webs, which were typically 100 yards long, were then laid on the bleaching greens to be whitened by the sun and the rain. They were watered regularly, a process known as “wet bleaching” and each mill had its own recipe for aiding the bleaching process, usually incorporating sour milk, buttermilk, urine and manure.

Linen webs being laid out on a Bleaching Green (Conrad Gill,1925 ‘The Rise of the Irish linen Industry’ Clarendon Press)

After two weeks, they were taken back inside for washing again. This practice was only done in spring and summer months. In 1725, a law was passed prescribing a closed season from mid-August to the beginning of February, during which no webs might be laid out to bleach. (Gill, 1925)

The number of bleaching greens in Ireland reached a maximum of 357 in 1787 but declined rapidly as bleaching methods continued to improve. By the 1850s, there were only 40 bleaching greens coping with many times the quantity of linen.

Flax to Linen – The Process

- April – May: Flax seeds sown densely to create taller plants.

- Mid-August: Flax plant pulled and stacked in bunches called “knee gates” to dry

- “Rippling”: The flax seed was removed

- “Retting”: The flax bundles were steeped in flax dams or ponds to allow the woody matter to decay away from the fibre bundles.

- “Scutching”: Beating the flax plant mechanically to remove the woody matter called “shive”.

- “Heckling”: The flax was then pulled through “heckling combs” which separated the locked fibres, making them straight, clean, and ready to spin.

- Spinning: The flax fibres were spun to make the yarn.

- Weaving: The yarn was woven on the loom to make the linen fabric.

- Bleaching: The brown linen webs were bleached to white.

- “Beetling”: The pounding of linen fabric to give a flat, lustrous effect. This was a part of the finishing process.

Flax Facts

- In 1814, flax acreage grown was listed as 100 acres in County Clare and 1750 acres in Co. Limerick.(Smith, 1988)

- 1796: Irish Linen Board published a list of nearly 60,000 flax growers of Ireland. No growers were listed in the Clonlara area.

- Ireland’s first manufactured export was linen.

- The success of the flax staple and its attendant textile industry is clearly expressed by the fact that by 1780, the value of exported linen yarn and flax was worth more than the combined values of exported cattle, meat, dairy products, and grain.(Murray, 1907)

- Linen is one of the world’s oldest fabrics. Mummies have been found wrapped in linen shrouds dating as far back as 4500 BC.

- The lifespan of a flax plant in a field from its first shoots to full maturity is 100 days.

- The blue flower of the flax plant is the symbol of the Northern Ireland National Assembly.(About Linen, 2020)

- Flax Linen sails were found on the great explorers’ ships – Admiral Lord Nelson and Captain Cook.

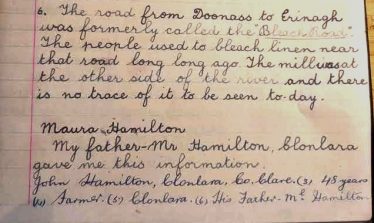

Extract from the Schools Collection by Maura Hamilton (National Folklore Collection)

The Memory Fades – The Mill Today

Tunnels in Existing Canal System

(Photo: Rose Hannan Feb 2020)

There is no evidence of the bleach mill building today at Waterpark. However, the canal system which provided the water to turn the mill wheels, and its four bridges, are still in place. Waterpark House also no longer exists. The only remaining features are the steps to the main house and some adjacent buildings.

Outflow from Mill back to the River Shannon.

(Photo: Rose Hannan Feb 2020)

Headrace of Bleach Mill Canal System (Photo:Rose Hannan Feb 2020)

Unanswered Questions

I hope to explore this subject into the future and these are some of the questions that I wish to pursue:

- Where in Northern Ireland did Hercules Brownrigg/Browning come from?

- Who invited him to Waterpark? Was it Lord Massy or was there a Phelps connection?

- Where did he live in Summerhill?

- Who were the Quinns and where did they come from?

- Who built (and when? – prior to 1760) the extensive shallow canal system? The tail race alone is 750 metres long. It also features tunnels, four bridges, and the mill itself. It was a big engineering project for the time.

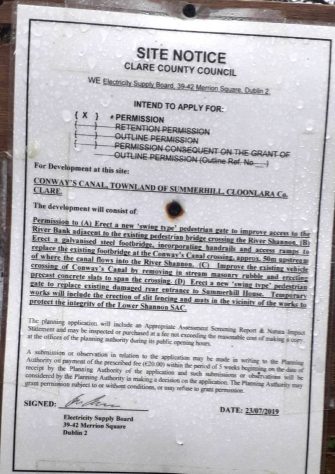

Planning Permission Notice at Waterpark (Photo:Rosemary Hannan)

Site of Waterpark House today (Photo: Rosemary Hannan)

Acknowledgements

Matthew Potter, Curator Limerick City Museum

Freddie Bourke, local historian, Clonlara

Mike McGuire, Librarian, Granary Library, Limerick

Peter Beirne, Local Studies Centre, Clare County Library, Ennis

The Ryan Family, Clonlara

Bibliography

About Linen. (2020, January 31). Retrieved from Ferguson’s Irish Linen: https://www.fergusonsirishlinen.com/pages/index.asp?title2=Interesting-Facts&title1=About-Linen

Bourke, F. (1998). The Famine Decade in Clonlara 1840-1850. Clonlara: Yardfield Books.

Gill, C. (1925). The Rise of the Irish Linen Industry. Ireland: Clarendon Press.

Goggin, B. (2020, January 31). The Doonass bleach mill and Conway’s Canal. Retrieved from Waterways Ireland: https://irishwaterwayshistory.com/about/irish-waterways-scenery/the-doonass-bleach-mill-and-conways-canal/

Hamilton, M. (1937). Roads in the District. The Schools’ Collection, 129. National Folklore Collection, UCD.

Landed Estates Database. (2020, January 31). Retrieved from NUI Galway: http://landedestates.nuigalway.ie/LandedEstates/jsp/property-show.jsp?id=2373

Leslie, R. J. (2018). The Irish Linen Industry. Stenlake Publishing Ltd.

Lewis, S. (1837). Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. London: S. Lewis & Co.

Murray, A. E. (1907). History of the Commercial and Financial Relations between England and Ireland from the Period of the Restoration Second Edition. London: King, London.

O’Connor, P. J. (1989). The Promotion of a Limerick Linen Industry 1760-1763. The Old Limerick Journal No. 26.

Smith, W. (1988). Flax Cultivation in Ireland, The Development and Demise of a Regional Style. In W. W. Smyth, Common ground: essays on the historical geography of Ireland presented to T. Jones Hughes. (pp. 234-252). Cork: Cork University Press.

Weir, H. W. (1989). Houses of Clare. Whitegate, Co. Clare: Ballinacurra Press.

Comments about this page

Part of my family the Phelps lived at Waterpark in the second half of the 19thc. They also had a hunting lodge at Broadford. Wondering if they purchased both at the same time from the Bindons. The Phelps were well established in Limerick and had family connections to the Harvey’s of Summerville House in Limerick. Best

Add a comment about this page