Quarries in Kilrush and Killimer

Michael Gilligan

Introduction

Quarries were a main source of employment in the Kilrush and Killimer area between the 1850’s and 1950’s. Working in the quarries was often the difference between starvation, emigration or a meagre living. This story is about the work, the workers and the lost opportunity by a local landlord, Crofton Moore Vandeleur, to save thousands of people from the workhouse and starvation.

The Quarries

In Kilrush and Killimer we had seven quarries that were in use at one stage or another. Moneypoint, Salthill, Knockerra and Tullagower in Killimer and The Cragh, and two more in Moyne in Kilrush. The bedrock in all is sandstone and shale. Moneypoint and Knockerra were the main employers, but the other quarries often employed up to fifty people during peak time. The following description concentrates on the quarries at Moneypoint, and Knockerra.

The Knockerra quarry was in use from the late 1700’s, producing mainly slate for local use. In the 1850’s it was expanded into a flag stone operation, which gave a lot more employment. Moneypoint was the biggest quarry in this area when it was in its prime and with so many working there, a small village was built on the site to house the workers. These houses were known as The Lane Houses. In 1855, Griffith’s valuation recorded twenty families living in the townland of Carrowdotia South. This was Vandeleur’s land, but it was leased out to Mary O Grady, for £100 a year.

Knockerra Quarry was famous for its colourful flag stone. Mr Talty, landowner and owner of Donogrogue Castle, opened the quarry to a larger market. He took the land in tenancy from Batt Culligan, the landlord at that time for the area. James MacLachlan, from Scotland, came to Knockerra as a foreman with a mining company to quarry flags in 1879. The mining company did not pursue the enterprise, but MacLachlan saw potential and decided to have a go on his own. He turned it into a major place for employment, during hard times.

Exporting

From the 1840’s onwards, the exporting of flag stone from Kilrush and Killimer grew and they were sent further afield. Quarries by the Shannon, like Moneypoint and Moyne, had their own quays for transporting the flag stone and slate to Limerick and around Ireland and Great Britain. If the flag stone was being exported to the continent or America it would be carted to Kilrush for loading on to larger boats.

The Railway Commissioners Survey of Ireland 1835, records that the annual produce from Moneypoint quarry was about 60,000 yards valued at £2,250 at quarry. From here 20,000 superficial (square) yards were shipped annually to Cork; 16,000 were conveyed by small boats (called Coasters) to Galway and Tralee, and 20,000 to Limerick of which 16,000 superficial yards were cubed and manufactured at Killaloe and then shipped to Dublin, London and Liverpool. All the Knockerra flagstone was carted to Kilrush and shipped to Scotland, England, Belgium, Holland and Germany. Flag stone from Moyne was exported to Scotland, mainly to Glasgow and Edinburgh for use as street paving. There was an attempt to export on a great scale to America but this was unsuccessful. The reason is given below.

Franklin and the Quarries

Mr Phenias Franklin, an Englishman, and his nine brothers were experts in marble quarrying. They owned quarries all over the world, including Carrara, Naples and Leghorn (Italy), Liverpool, London and Bristol, (England), New York and California, (America), and Galway (Ireland). Their quarry in Galway was called the “Black Marble Works “. They exported finished marble from Galway, which was used in the construction of the great staircase in the Duke of Hamilton’s mansion in Scotland, and also for the base for the magnificent monument to Napoleon in Paris.

The Clash

Franklin came to Kilrush in the mid 1840’s, and saw great potential in the local quarries. He had the expertise to develop the quarries which would result in a growth in local employment. His main problem was the landlord Crofton Moore Vandeleur.

A report in the “Limerick and Clare Examiner” newspaper on the 6th February 1850, explains the situation:

“The quarry at Kilrush does not yield marble, but it produces large and valuable flags of excellent quality, and adapted to many public, domestic and mercantile uses to which they are applied. How long Mr Vandeleur would have taken to digest the project of making a market for their disposal beyond the Atlantic we need hardly declare. For we are instructed, Franklin has put in execution, that no later than Monday he chartered a vessel to take Kilrush flags to New York, and he is about to engage another with a like view. For ten days he has nine horses and carts drawing those flags to the waterside and has given employment in raising and preparing them, the fathers of nearly three hundred families. Take each family to be five, and you have about as many persons supported by the works of a single enterprising Englishman, as all the exterminators and their nominees of the Kilrush Board of Guardians do not support, as they should be supported within the walls of the workhouse. How many more such resources as the Flag Quarry are continued in the Union we cannot count, but if there were no other, the river, the land, and the sea are at hand and ever were, and upon these if the exterminators had common humanity and plain common sense, they could have employed reproductively the 24,000 occupiers whom they reduced to dependence and are now cutting off by degrees from the very face of the earth. ” [Vandeleur was also head of the Kilrush Board of Guardians]

Crofton Moore Vandeleur was evicting hundreds of people from their houses and land every week during the famine. Workhouses were overflowing and riddled with disease, which caused many more to die. Vandeleur through his actions in evicting people from their homes and land, caused great hardship in this area, which led to many people dying, emigrating or entering the workhouse. At the same time, he was benefiting from berthing fees from all the boats loading and unloading in Kilrush. This is what Phenias Franklin wanted to turn around, but without any success.

Quarry Machinery and Tools

In the early years, quarrying was a very hard and rough labour, with a lot of accidents, because of primitive equipment. The workers used hammers, wedges, chisels and tripods for lifting and derrick winches and stone carts for bringing flagstones to boats. This eased the hardship but not by much.

The quarries were closed during World War II, as a result of local construction coming to a standstill and also because export had come to a halt because of the dangers of sea travel. After the war, a few of the quarries began to be used again by the County Council, but on a smaller scale to produce stone and gravel for road making. By this time, they had steam operated stone crushing machines and explosives were used to split the rock, which meant bigger amounts produced in a shorter time.

The Quarry Stone

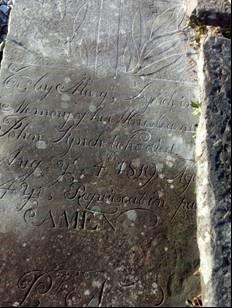

The quarried stone was used locally for everything, including pavements, roofs, graves and coffin drains on farms and roads. Even gates were hung from a large flag stone from the local quarry. There was no waste in the quarry as different size flags had different purposes. The smaller flags were mainly used for coffin drains or crushed for gravel for the roads. The flag stones were used for grave stones locally and we can see the beautiful engravings that have survived for over 200 years, which shows the toughness and slow wearing of this Moneypoint flag. That’s why it was mainly exported for pavements.

That Kilrush and West Clare were only second to Skibbereen as the hardest hit area during The Great Famine, is a statistic that never should have happened. We were blessed with an abundance of quarries, that had top quality flagstones and slate, bogs, and a port as good as any rural port in Ireland. The potential of saving so many lives by opening the quarries to produce maximum output would have given so many families a means to survive and ride out the famine. By using the Kilrush quays for exporting vast amounts of flagstone, and slate, that would have been exported throughout Great Britain, Europe and America. Instead the port was used for exporting vast amounts of grain, fodder, butter, and live animals to the main ports scattered throughout England.

Phenias Franklin saw a way to save thousands of lives, unfortunately he hit a stone wall in the local landlord Croften Moore Vandeleur, who had prevented Franklin from leasing his quarries.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page